[Heathen Chinese is one of our talented monthly columnists. Monthly he brings you insight and analysis about issues coming from within or affecting our collective communities. If you enjoy his work, consider donating to our fall fund drive today. It is your dollars and your support that make it possible for Heathen Chinese and our columnists to continue their dedicated work, and for us to bring on more talented monthly voices. Please donate today and share the campaign! Thank you.]

2016 marks the eightieth anniversary of the beginning of the Spanish Civil War and the Spanish Revolution. When Franco led his fascist forces against the Second Spanish Republic in July 1936, anarchist militias simultaneously fought the fascists and seized large swathes of Southern and Eastern Spain, overthrowing local authorities and collectivizing wealth. One of the most passionate and dedicated of these militias, the Iron Column, was formed largely of liberated prisoners and included women within its ranks.

While the Iron Column fought the fascists on the front lines, however, their supposed comrades were stabbing them in the back. The syndicalists of the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) joined the Republican government in September 1936, with three CNT members taking positions as ministers. In March 1937, the Iron Column, previously organized along egalitarian lines, was ordered to submit to incorporation into the Republican Army and accept the leadership of Republican officers hostile to their revolutionary ambitions. One of the “uncontrollables” of the Iron Column published a denunciation of this betrayal, entitled “A Day Mournful and Overcast,” in Nosotros, the daily newspaper of the Column.

The uncontrollable introduced himself as “an escaped convict from San Miguel de los Reyes, that sinister prison, which the monarchy set up in order to bury alive those who, because they weren’t cowards, would never submit to the infamous laws dictated by the powerful against the oppressed.” He had been imprisoned at the age of twenty-three “for revolting against the humiliations to which an entire village had been subjected. In short for killing a political boss.”

In this detail of his life story, he closely resembles the Chinese warrior Guan Yu, who was later deified as Guan Di and is closely associated with loyalty and righteousness. In the Ming Dynasty novel Romance of Three Kingdoms, Guan Yu explains why he left his hometown, for “there was a man from a wealthy family who was acting like a big shot and bullying everybody, I ended up killing him. I had to become a fugitive, and have been living the life of an itinerant mercenary for the past five or six years.” Like Guan Yu, the uncontrollable rebelled and fought back against injustice in his home village, and suffered the consequences for his action: he was imprisoned for eleven years before anarchists opened the gates of the penitentiary. The word “rebel,” incidentally, comes from the Latin prefix re- (opposite, against, or again) added to bellare (to wage war): thus, it literally means “to fight back.”

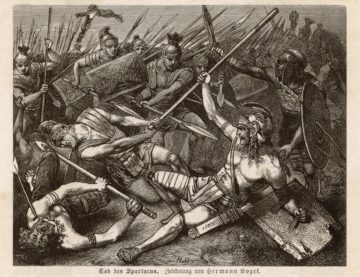

The uncontrollable joined the militia that had liberated him, and, like Spartacus and his fellow rebels stripping weapons from the Roman legions they defeated (Life of Crassus 9.1), he armed himself with a rifle seized from a slain fascist. While fighting the fascists, the Iron Column also “changed the mode of life in the villages through which we passed – annihilating the brutal political bosses who had robbed and tormented the peasants and placing their wealth in the hands of the only ones who knew how to create it: the workers.” The methodology and members of Iron Column, however, were denounced by their enemies:

We have been treated like outlaws, and accused of being “uncontrollable”, because we did not subordinate the rhythm of our lives, which we desired and still desire to be free, to the stupid whims of those who, occupying a seat in some ministry or on some committee, sottishly and arrogantly regarded themselves as the masters of men.

The reference to those “occupying a seat in some ministry” clearly referred to the supposedly anarchist-syndicalist CNT, for it was not only fascists but also anti-fascists who condemned the Iron Column: “Not only the fascists considered us dangerous, because we treated them as they deserved, but in addition those who call themselves anti-fascists, shouting their anti-fascism until they are hoarse, have viewed us in the same light.” And the uncontrollable knew exactly what kind of people love to shout their anti-fascism until they are hoarse: “people who wish to be regarded as leaders.”

![Lucia Sanchez Saornil, one of the founders of Mujeres Libres. [Public Domain]](http://wildhunt.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Luic_San_Saorn_1933.jpg)

Lucia Sanchez Saornil, one of the founders of Mujeres Libres, an anarchist women’s organization that maintained independence from the CNT. The process of militarization re-established the gender roles that Mujeres Libres sought to destroy. [Public Domain]

The uncontrollable is a pariah. And moreover, the uncontrollable is a mystic seeking to “penetrate the obscurity of the fields and the mystery of things” at night while fighting the fascists by day:

On some nights, on those dark nights when armed and alert I would try to penetrate the obscurity of the fields and the mystery of things, I rose from behind my parapet as if in a dream, not to awaken my numbed limbs, which having been tempered in pain are like steel, but to grip more furiously my rifle, feeling a desire to fire not merely at the enemy sheltered barely a hundred yards way, but at the other concealed at my side, the one calling me comrade, all the while selling my interests in most sordid a manner, for no sale is more cowardly than one nourished by treason.

On those nights, the uncontrollable was possessed by the urge to run wild and destroy all that sought to grind him and his comrades down:

And I would feel a desire to laugh and to weep, and to run through the fields, shouting and tearing throats open with my iron fingers, just as I had torn open the throat of that filthy political boss, and to smash this wretched world into smithereens, a world in which it is hard to find a loving hand to wipe away one’s sweat and to stop the blood flowing from one’s wounds on returning from the battlefield, tired and wounded.

There is an ancient Greek word for this kind of hands-on dismemberment: σπαραγμός. Sparagmos is associated in literature with the Dionysiac cults, which contained many women and slaves, just as the Iron Column was comprised of ex-prisoners. Euripides wrote in Bakkhai that the mainads needed no weapons but their hands to hunt their prey:

They, with hands that bore no weapon of steel, attacked our cattle as they browsed. Then wouldst thou have seen Agave mastering some sleek lowing calf, while others rent the heifers limb from limb. Before thy eyes there would have been hurling of ribs and hoofs this way and that; and strips of flesh, all blood-bedabbled, dripped as they hung from the pine-branches. Wild bulls, that glared but now with rage along their horns, found themselves tripped up, dragged down to earth by countless maidens’ hands. The flesh upon their limbs was stripped there from quicker than thou couldst have closed thy royal eye-lids.

But it is not only destruction that characterizes the Dionysian spirit, but “the wildly irrepressible desires we carry in our hearts to be free like the eagles on the highest mountain peaks, like the lions in the jungle.”

![Dionysos mosaic [Ancient Images / Flickr]](http://wildhunt.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Dionysos-Chariot-360x255.jpg)

Dionysos mosaic [Ancient Images / Flickr]

I would abandon myself joyfully to dreams of adventure, beholding with heated imagination a world that I knew not in life but in desire, a world that no man has known in life but that many of us have known in dreams. And dreaming, time would fly by, and my body would stand weariness at bay, and I would redouble my enthusiasm, and become bold, and go out on reconnaissance at dawn to find out the enemy’s position, and…. All of this in order to change life, to stamp a different rhythm onto this life of ours; all of this because men could be brothers and I among them; all of this because joy that surges forth even once from our breasts must surge out of the earth, because the Revolution, this Revolution that has been the guiding light and watchword of the Iron Column, could soon be tangible reality.

The word “enthusiasm” also comes from ancient Greek: ἐνθουσιασμός denotes the condition in which a god (θεός) is inside (ἐν) a person. Compare the previous quote with a passage from Friedrich Nietzsche’s Birth of Tragedy:

Under the magic of the Dionysian, not only does the bond between man and man lock itself in place once more, but also nature itself, now matter how alienated, hostile, or subjugated, rejoices again in her festival of reconciliation with her prodigal son, man. The earth freely offers up her gifts, and the beasts of prey from the rocks and the desert approach in peace. The wagon of Dionysus is covered with flowers and wreaths. Under his yoke stride panthers and tigers.

If someone were to transform Beethoven’s Ode to Joy into a painting and not restrain his imagination when millions of people sink dramatically into the dust, then we could come close to the Dionysian. Now is the slave a free man, now all the stiff, hostile barriers break apart, those things which necessity and arbitrary power or “saucy fashion” have established between men. Now, with the gospel of world harmony, every man feels himself not only united with his neighbor, reconciled and fused together, but also as if the veil of Maja has been ripped apart, with only scraps fluttering around before the mysterious original unity. Singing and dancing, man expresses himself as a member of a higher unity. He has forgotten how to walk and talk and is on the verge of flying up into the air as he dances. The enchantment speaks out in his gestures.

In both of these texts, we find sympathetic magic between the joy of the earth and the liberation of humans, the possibility of universal camaraderie between human and human, and a dreamlike transcendence that becomes incarnate within material reality.

Dionysian methodologies of warfare cannot be described as “non-violent,” but they supersede the linearity of rigid militarization by striking where unexpected, by changing the very time and space within which the “battle” is waged. Euripides’s mainads first and foremost caused disruption by abandoning the οἶκος (oikos), the household centered around slavery and gender roles, whence we derive the word “economy:” management of the οἶκος.

But when pursued, they fought “with the thyrsus, which they hurled, caused many a wound and put their foes to utter rout, women chasing men, by some god’s intervention. Then they returned to the place whence they had started, even to the springs the god had made to spout for them; and there washed off the blood, while serpents with their tongues were licking clean each gout from their cheeks.”

Another individual known for having snakes coil about his face, the Thracian gladiator Spartacus, whose wife was a prophetess, also won a battle by a Dionysian miracle. Spartacus and his fellow runaway slaves, who were primarily of Thracian and Gaulish origin, were besieged on top of Mount Vesuvius:

But the top of the hill was covered with a wild vine of abundant growth, from which the besieged cut off the serviceable branches, and wove these into strong ladders of such strength and length that when they were fastened at the top they reached along the face of the cliff to the plain below.

Descending on these ladders of wild vines, the rebels caught the Roman legion by surprise and defeated them in battle. Like the Iron Column, they were supported by the locals: “they were also joined by many of the herdsmen and shepherds of the region, sturdy men and swift of foot, some of whom they armed fully, and employed others as scouts and light infantry.” The escaped slaves and shepherds of Vesuvius were literally anti-fascists: Roman officials were preceded by lictors carrying fasces as symbols of their political authority.

Death of Spartacus, Hermann Vogel. [Public Domain]

Michael Kimble, a black gay anarchist incarcerated at Holman, writes that prisoners’ struggle will not always be non-violent, echoing the Iron Column in his uncontrollability: “If your solidarity and support is predicated on prisoners being ‘non-violent,’ we don’t want or need it, because you are trying to control us.”

The Iron Column’s revolutionary war against fascism and prisons and the society that produces both is alive and well. And it is once again being fought by partisans, by people who desire first and foremost to change their own lives, “to stamp a different rhythm onto this life of ours.” Ill Will Editions writes that the concept of the “partisan” is “best understood not as a splitting of a totality into competing parts or factions each defined via mutually contested claims over the management of the whole, but rather as the intensification of asymmetrical differences that were already there within the way we live.”

The Polytheist and Heathen milieus are plagued by “people who wish to be regarded as leaders” of movements, who wish to claim “management of the whole.” Some of them wish to maintain the supposedly apolitical nature of the whole, others to defend the whole against the very real threat of fascist infiltration. Both positions accept and reify the continued existence of the πόλις (polis), which exists only in contrast to actual communities and traditions. My position is not apolitical, but anti-political.

Mujeres Libres wrote, “To be an anti-fascist is too little; one is an anti-fascist because one is already something else.” Like their syndicalist predecessors who became Ministers, those who claim to be anti-fascist because they are aspiring managers do not seek the “different rhythm” of life that I seek. The uncontrollables of the Iron Column speak from their mass graves, warning us never to trust these would-be politicians:

History, which records the good and evil that men do, will one day speak. And History will say that the Iron Column was perhaps the only column in Spain that had a clear vision of what our Revolution ought to be. It will also say that of all columns, ours offered the greatest resistance to militarization, and that there were times when because of that resistance, it was completely abandoned to its fate, at the front awaiting battle, as if six thousand men, hardened by war and ready for victory or death, should be abandoned to the enemy to be devoured.

History will say so many, many things, and so many, many figures who think themselves glorious will find themselves execrated and damned!