“6-3-6: The concept of politics has then become completely absorbed into a war of spirits.” —Nietzschemanteion

“6-3-6: The concept of politics has then become completely absorbed into a war of spirits.” —Nietzschemanteion

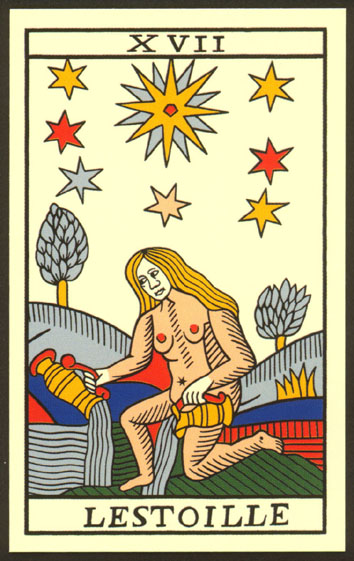

The Star, Tarot de Marseille, Jean Noblet. Public Domain.

Or as Diane di Prima wrote, “the war that matters is the war against the imagination/all other wars are subsumed in it.” The enemy is despair, but secular ideologies of progress will never be enough to keep the enemy at bay. It takes a certain kind of sympathetic magic to counter despair.

The seeds of what one is fighting for must be contained in one’s actions. If you want to live in a world where the relationships between the gods, the ancestors, the land and human beings are in harmony, then you have to put effort into strengthening and balancing those relationships right now.

We need to solidify our relationships with those who are closest to us first. Small numbers should not be seen as a deterrent to action, but an asset. In the words of the anonymous authors of At Daggers Drawn:

The method of spreading attacks is a form of struggle that carries a different world within it. To act when everyone advises waiting, when it is not possible to count on great followings, when you do not know beforehand whether you will get results or not, means one is already affirming what one is fighting for: a society without measure.

This, then, is how action in small groups of people with affinity contains the most important of qualities–it is not mere tactical contrivance, but already contains the realization of one’s goal. Liquidating the lie of the transitional period means making the revolt itself a different way of conceiving relations.

If we refuse centralization we must go beyond the quantitative idea of rallying the exploited for a frontal clash with power. It is necessary to think of another concept of strength–burn the census lists and change reality.

And if your motivation is love, then your actions in defending your loved ones must contain that love within them. Morpheus Ravenna expressed this concept well:

In answer to the questions about why I urge us to fight, and whether I am devaluing love by focusing on battle readiness, here is my answer. What I am encouraging – strength in kinship, survival skill, and ability to defend what we love – these things are of benefit whether we ever meet trouble or not. My answer is that to fight for love is love in action.

Walls and Eyes

“To make the force of your army’s attack like a grindstone crushing an egg, you must master the substantial and the insubstantial.”

—Sun Zi, The Art of War

Formation with two eyes. Public Domain.

In the Chinese board game 围棋 (wéiqí, more commonly known as Go in Japanese and English), formations are captured by being surrounded by enemy stones. To make capture impossible, a formation must contain two empty spaces, or “eyes,” within it. Formations with no eyes, or only a single eye, are vulnerable.

When surrounded by enemies, walls are necessary to delineate and defend one’s community. But more important than the walls is the space within it, the space that makes room for the gods and spirits, that makes room for worship and dancing and feasting, that makes room for the hearth fire for which one fights.

In my article on Tupac Shakur, I compared Thugz Mansion to the Isles of the Blessed, an afterlife where one meets ones heroes (in the ancient Greek sense) face to face. But upon relistening to the song in a ritual setting, I realized that the song also contains this message: given the failure of political attempts to seize physical space, our only recourse is to seek spiritual refuge, to seek out Thugz Mansion while still living: “Will I survive all the fights and the darkness?/Trouble sparks, they tell me: ‘Home is where the heart is.'”

Trump’s wall contains a single eye, but it is the eye on the back of the dollar bill, the eye that surveils an empire built by the labor of slaves on land whose sovereignty has been and continues to be violated. America’s empty space is a spiritual vacuum, a severance from the spirits of the land, and its walls are destined to fall.

The American empire is the direct descendant of the Roman, tracing the legitimacy of its imperium from Protestant England to the Vatican to the Western Roman Empire. The American republic consciously modeled itself on its Roman predecessor: fasces flank the flag in the House of Representatives, and are featured prominently throughout government architecture and insignia. However, Roman myth and history also contain many interesting stories that partisans on the other side of the spirit war can learn from as well.

The collapse of an empire is an opportunity for new communities to emerge and carve out their own spaces, like the Kurds of Rojava have done in the Syrian civil war. To survive, however, these new communities will need sources of strength and resiliency.

Resiliency

“I know my gods are real. They have enabled me to withstand you.”

—James Baldwin, No Name In The Street

The English word “resiliency” is derived from the Latin resilio, meaning “to leap or spring back.” The Latin verb salio, “to leap,” is also the origin of the name of the Salii, a priesthood of twelve youths who served Mars Gradivus. Livy writes that the Salii were ordered by Numa to bear arms and “to carry the celestial shields called ancilia, and to go through the city singing songs, with leaping and solemn dancing,” and that the time period in March “during which the sacred shields are moved” was considered “too holy for marching,” at least for the Salian priests themselves. The same taboo is also mentioned in the histories of Polybius, Tacitus and Suetonius, and also applied during October, which was also when the festival of Armilustrium was held for the purpose of cleansing weapons. The Salii were also associated with lavish banquets, as can be seen in one of Horace’s odes.

The association of the leaping and dancing priests of Mars with annual religiously-mandated periods of peace and banqueting suggests that this ritual distinction between war and peace is important to the “springing back” intrinsic to resiliency. The ability to set down shields and armor and weapons is crucial. It also calls to mind the temple of Janus, the doors of which theoretically also marked a distinction between war and peacetime, but in practice were almost always open. Plutarch writes:

There is a temple to him in Rome, which has two doors, and which they call the gate of war. It is the custom to open the temple in time of war, and to close it during peace. This scarcely ever took place, as the empire was almost always at war with some state, being by its very greatness continually brought into collision with the neighboring tribes. (XX)

Aeneas carrying Anchises. Public Domain.

The United States, too, has remained in a continuous state of emergency for many years. Rome’s permanent war traced itself to two different foundation myths, one involving the wolfish fratricide of Romulus and Remus (which finds a strange parallel in the Icelandic Prose Edda story of Loki’s sons Váli and Narfi/Nari), and the other claiming descent from Aeneas, the son of Venus and Anchises, who escaped Troy with his father and his household Gods on his back, a model for pious resiliency if ever there was one.

The latter story is particularly ironic considering how many other tribes and peoples Rome conquered, but like Aeneas, many of those tribes found ways to continue the worship of their gods and goddesses even in defeat. For example, hundreds of inscriptions to the Matronae and the Matres bear epithets that are clearly derived from Germanic or Gaulish languages. River Devora writes about how the Matronae act as a collective of many individuals:

The Matronae and Matres were a collective of many deities, each one specific, regional, local, and distinct. Each individual goddess had her tribe, her land feature, her individual relationships with others from her specific pantheon etc. Each goddess was a unique, standalone goddess. The Matronae functioned as a collective of individual goddesses, each of whom had their own separate stories, attributes and even pantheons. The individual goddesses crossed regional and tribal lines to function as a multi-cultural, multi-regional, and multi-traditional collective.

The collective which supports and strengthens the individual rather than effacing their identity, and which operates across cultures and traditions respectfully, holds another important piece to the question of resiliency. One of the Matronae epithets that combines Latin and Germanic elements, Veteranehae, again recalls the transition between war and peace discussed above. Roman veterani, retired soldiers, were often recruited from conquered tribes, and their worship of the multi-cultural Matronae makes perfect sense given this context.

In China, the syncretic Daoist-Buddhist-Manichaean White Lotus Society overthrew the Yuan (Mongol) Dynasty, then continued to wage clandestine insurgencies against the Ming and Qing (Manchu) Dynasties for centuries, all the while advocating the abolition of gender. “Its practices included medical healing, sitting and breathing exercises, martial arts, and the chanting of spells and charms.”

Collapse

“And ‘mid this tumult Kubla heard from far/ancestral voices prophesying war!”

—Samuel Taylor Coleridge, “Kubla Khan”

Hunnish chamfron, bridle mounts and whip handle. Public Domain.

Many cross-cultural formations arose during the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, most famously the Hunnic Empire, a confederacy of Huns and Alans and Germanic tribes including the Ostrogoths and the Gepidae. Attila bears the unique distinction of being attested to in Roman histories, in the Anglo-Saxon poem Widsith, in the Norse sagas Atlakviða, Volsunga saga and Atlamál, and in the Medieval German poem Nibelungenlied.

The Huns intermarried with other tribes, and allowed Christian missionaries into their territory “in a spirit of religious tolerance,” despite maintaining their traditional religious practices, such as divination by “entrails of cattle and certain streaks in bones that had been scraped,” possibly a form of scapulimancy similar to that practiced in Shang Dynasty China.

The Armenian chronicler Moses Daskhuranci, who visited the Huns of the Caucusus, described tree-worship, burnt horse sacrifices to “Tʾangri Khan, called Aspandiat by the Persians,” self-inflicted lacerations (also attested to by the Roman historian Priscus) and sword fights during funerals, and “sacrifices to fire and water and to certain gods of the roads, and to the moon and to all creatures considered in their eyes to be in some way remarkable.” It was not until the 680s that the Huns of the Caucasus converted to Christianity, destroyed their sacred groves and idols, and promised “to burn the sorcerers and wizards who will not adopt the faith, and [to] put to the sword any person who acts like a pagan.”

The Saxons fought as Roman foederati against the Huns at the battle of the Catalaunian Plains, but following the withdrawal of Roman forces from Britain, they and the Angles migrated to and settled in Britain. Bede’s On the Reckoning of Time gives a few fragments of information about the religious practices of the Anglo-Saxons: they conducted ceremonies on Modranicht, mothers’ night, which coincided with Christmas Eve; March was named Hredmonath after the goddess Hreða, who received sacrifices that month; and April was named Eosturmonath after the goddess Eostre, whose feasts were held at that time.

Interestingly, the name element “Hreð-” also appears in the term Hreðgotan, a name used in two Old English poems to refer to the Goths, who are described as fighting against Attila in Widsith and as fighting with the Huns against (anachronistically) Constantine in Elene (87-89). The possibly related terms Hreiðgotar and Reiðgotaland are found in an Eddaic poem and in numerous sagas respectively, and an inscription from Rök in Õstergötland, Sweden, mentions the Hraiðkutum in conjunction with Theoderic and the Maerings, whom the Old English poem Deor also link together (90). These parallel transmissions remind us that power of poetry for the preservation of historical and mythical memory should never be underestimated as another factor contributing to resiliency. The oral tradition of the Rigveda and the Homeric recollection of Bronze Age boar’s tusk helmets that were long gone by the time the Iliad was written are yet further examples of poetry’s miraculous endurance.

The Huns and the Anglo-Saxons were both in turn violently converted themselves, but nonetheless, they provide historical precedent for polytheist, animist, tree-worshiping tribal confederacies “springing back” and seizing space from the collapse of a monotheist empire. Nietzsche wrote that “there will be wars such as the earth has never seen.” He may well be right, but we would do well to study the lessons of our ancestors.

* * *