I write this as a devotee of war gods with the purpose of examining various theories about the State’s monopoly of violence, counter-insurgency and warriorship. This essay is written in the aftermath of the killing five police officers during a Black Lives Matter demonstration in Dallas July 7 and the killing of three police officers in Baton Rouge July 17, the same city where Alton Sterling was killed July 5.

These two targeted attacks have highlighted other incidents in which police officers have been shot. For instance, a man in Oakland is accused of shooting at a police officer July 23, “solely because she was a police sergeant in uniform.” Several law enforcement officers have also been shot and killed while attempting to transfer prisoners or detain individuals: for instance, two courthouse bailiffs in Michigan were killed by an inmate July 11, a Kansas City police captain was killed July 19, and a San Diego police officer was killed July 28.

The National Law Enforcement Officer Memorial Fund reports that 14 “ambush-style” attacks have resulted in police deaths this year, and that “for the first time in three years, traffic-related fatalities were not the leading cause of law enforcement deaths during the first half of the year,” having been surpassed by firearms-related fatalities. However, it is also worth keeping in mind that a Bureau of Labor Statistics study analyzing 2014 data found that police officers were not among the top ten “civilian occupations with high fatal work injury rates.” Whether police officers should be considered civilians or not, however, is debatable.

State Monopoly of Violence

After the shooting in Dallas, Barack Obama gave a speech in which he said, “Let’s be clear: There is no possible justification for these kinds of attacks or any violence against law enforcement.” By arguing that “justification” does not exist for such acts, Obama actually shifts the discourse in an interesting direction: the question is not whether violence is justified or not, but whether or not it is sanctioned by the State.

In his essay “Politics as a Vocation,” Max Weber defines a state as “a human community that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory” (1). The word “legitimate,” of course, is tricky, but Weber clarifies that he simply means what is “considered to be legitimate.” In other words, there is a bit of a circular definition, since it is precisely the State and those under its rule that are doing the “considering.”

The philosopher Walter Benjamin, in his “Critique of Violence,” draws a very similar distinction between sanctioned and unsanctioned violence:

One might perhaps consider the surprising possibility that the law’s interest in a monopoly of violence vis-a-vis individuals is not explained by the intention of preserving legal ends but, rather, by that of preserving the law itself; that violence, when not in the hands of the law, threatens it not by the ends that it may pursue but by its mere existence outside the law. (281)

For example, even though vigilantism often pursues similar ends as the law (and sometimes works with individuals within government, in practice), in theory, it ultimately threatens the State’s monopoly of violence. This is particularly the case when it comes to police officers. The State reserves the right to prosecute its own, discouraging vigilantism; yet sometimes protects even the vigilantes and lawbreakers within its own ranks.

Obama claimed that “police in Dallas were on duty doing their jobs keeping people safe during peaceful protests.” By emphasizing that the protests were peaceful, he means that they did not attempt to usurp the violence that is reserved for police officers, who are simply “doing their jobs” when they use violence.

The implications of accepting the State’s desired monopoly of violence are perhaps best illustrated by one of Aesop’s fables:

![Etching by Wenceslaus Hollar [Wellcome Trust / Wikimedia]](http://wildhunt.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/A_wolf_is_biting_a_ram-360x482.jpg)

Etching by Wenceslaus Hollar [Wellcome Trust / Wikimedia]

The wolves sent messengers to the sheep, offering to swear a sacred oath of everlasting peace if the sheep would just agree to hand over the dogs for punishment. It was all because of the dogs, said the wolves, that the sheep and the wolves were at war with one another.

The flock of sheep, those foolish creatures who bleat at everything, were ready to send the dogs away but there was an old ram among them whose deep fleece shivered and stood on end. ‘What kind of negotiation is this!’ he exclaimed. ‘How can I hope to survive in your company unless we have guards? Even now, with the dogs keeping watch, I cannot graze in safety.’

As Weber’s definition suggests, however, not every would-be State’s claim to exercise a monopoly on violence is successful. Counter-insurgency theory never takes the State’s monopoly of violence for granted: it is always threatened and contested, and must be maintained through the use of force.

Counter-Insurgency Theory and War Gods

Counter-insurgency theory de-emphasizes the importance of the physical occupation of space, instead focusing on the ability to mobilize force. For example, in “Offensives, Ground Taken and the Assumption of Frontal Warfare,” the Institute for the Study of Insurgent Warfare posits that “the ability to mobilize force collapses not because space is occupied, but because supply logistics cannot be maintained, casualties degrade the ability to fight, desertions and mutiny break down force logistics and the capacity to contain crisis is exhausted”(5).

The recent battle on the Bosphorus Bridge in Istanbul, for example, showed that the mere physical occupation of the bridge by soldiers participating in the attempted coup did not achieve victory automatically. The blockade of the bridge instead crumbled due to a confluence of factors, including the ability of the pro-Erdogan forces to mobilize greater force against them.

Policing, too, exists as an ability to mobilize force, and thus should also be analyzed through the lens of counter-insurgent warfare. Tom Nomad writes about the projection of force through technology:

There are not ever enough police to cover terrain completely. Take a city like New York, which has tens of thousands of police; this number is not nearly enough to actually cover all space simultaneously. As such, police logistics are largely based on the attempt to project throughout space. This, historically, has been achieved through the combination of four different technologies in modern police operations; transportation, communications, weapons and surveillance.

As participants in insurgent and counter-insurgent warfare, both police officers and those who engage in armed conflict with them fall within the sphere of influence of gods interested in and associated with war.

Within law enforcement circles, there are those who dislike the term “warrior” itself and those who would “embrace” it. That this tension exists at all is interesting. Police officers can sometimes straddle the line between hired killer and bureaucrat, exemplifying the worst elements of each while accepting the responsibilities of neither. A warrior or soldier would accept the inevitability of enemies and open conflict, without claiming a monopoly of violence.

Benjamin writes of a similar oddity within the institution of policing. He classifies what he calls “violence as a means” into two categories: lawmaking, which requires victory in battle, or law-preserving, which requires “the restriction that it may not set itself new ends [i.e. become a new law unto itself]” (286). However, he writes, “police violence is emancipated from both conditions,” even though it combines both functions. That the police are law-preserving is evident, but in moments of crisis, the police can exercise the “assertion of legal claims for any decree.” For example, he writes, “the police intervene ‘for security reasons’ in countless cases where no clear legal situation exists.”

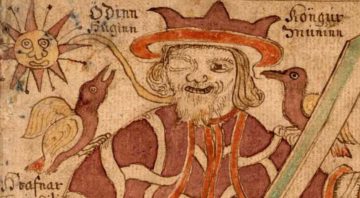

Odin. [Ranveig / Wikimedia]

long life to the Ulstermen

woe to the Irish

woe to the Ulstermen

long life to the Irish (Táin Bó Cúailnge)

In Introduction to Civil War, Tiqqun writes that traditional societies would not even understand the modern legalistic view of “violence,” let alone the State’s attempted monopoly of force.

“Violence” is something new in history […] Traditional societies knew of theft, blasphemy, parricide, abduction, sacrifice, insults and revenge. Modern States, beyond the dilemma of adjudicating facts, recognized only infractions of the Law and the penalties administered to rectify them. (34)

Therefore, Tiqqun declares that “for us, ultimately, violence is what has been taken from us, and today we need to take it back.” When they clarify “for us,” they do so deliberately. Referring to the etymology of Latin hostis (in early Latin, a stranger; in Classical Latin, a public enemy) from the Proto-Indo-European root *ghos-ti-, which could be used to mean stranger, guest or host, Tiqqun argues that civil war creates a situation where one is forced “to leave the sphere of hostility and thereby becomes a friend—or an enemy” (46).

To this effect, Introduction to Civil War begins with an epigram from Solon of Athens, who wrote in the Constitution of Athens that “Whoever does not take sides in a civil war is struck with infamy, and loses all right to politics.” Like the bat in the Aesop’s fable, one must take a side and stick with it. By civil war, however, Tiqqun refers not to a clash between States, but between “parties,” in the old-fashioned sense of “factions” (33).

In this article, I do not seek to convince anyone to switch sides, only to be clear about which side they are on. Let’s have no more of this lie that there are no sides, that there is only the untouchable State. Counter-insurgency theory teaches us that “in this attempt to project through space policing necessarily generates conflict” (Nomad). Conflict is inevitable.

Tiqqun’s argument that this State monopoly of violence is a modern concept is reinforced by Weber, who is most famous for his book The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. He links (perhaps a bit predictably) the authoritarian state to Protestantism:

Protestantism, however, absolutely legitimated the state as a divine institution and hence violence as a means. Protestantism, especially, legitimated the authoritarian state. Luther relieved the individual of the ethical responsibility for war and transferred it to the authorities. To obey the authorities in matters other than those of faith could never constitute guilt. (25)

However, Weber argues, the fundamental problem is that “we are placed into various life-spheres, each of which is governed by different laws. Religious ethics have settled with this fact in different ways.” Weber suggests that historical Hellenic polytheism was more comfortable with different deities ruling different life-spheres, while Hinduism took the approach of making “each of the different occupations an object of a specific ethical code.” For the warrior caste discussed by Krishna and Arduna in the Bhagavad-Gita, he writes, warfare was actually a religious duty:

Hinduism believes that such conduct [i.e. warfare, for those within the warrior caste] does not damage religious salvation but, rather, promotes it. When he faced the hero’s death, the Indian warrior was always sure of Indra’s heaven, just as was the Teuton warrior of Valhalla. The Indian hero would have despised Nirvana just as much as the Teuton would have sneered at the Christian paradise with its angels’ choirs. (25)

Like the warriors mentioned by Weber, one of the shooters seemed unafraid of his death as well. A day before the attack, he tweeted, “Just bc you wake up every morning doesn’t mean that you’re living. And just bc you shed your physical body doesn’t mean that you’re dead. Don’t let someone get comfortable with disrespecting you.” These tweets echo the warrior ethic found in the Hávamál:

16. A cowardly man

thinks he will ever live,

if warfare he avoids;

but old age will

give him no peace,

though spears may spare him.129. I counsel thee, Loddfafnir,

to take advice,

thou wilt profit if thou takest it.

Wherever of injury thou knowest,

regard that injury as thy own;

and give to thy foes no peace.

This column was made possible by the generous underwriting donation from Hecate Demeter, writer, ecofeminist, witch and Priestess of the Great Mother Earth.