The massacre in Orlando was an act of war, but how are the sides of the war delineated? Donald Trump, who declared in March that, “I think Islam hates us,” frames the war as Islam against the West. After the Orlando mass shooting, Trump again promised that if elected President, he would use his power to ban “immigration from areas of the world when there is a proven history of terrorism against the United States, Europe or our allies, until we understand how to end these threats.” Trump also accused Muslim communities in the United States of failing to report the “bad” Muslims whom he claimed were known to those communities: “Muslim communities must cooperate with law enforcement and turn in the people who they know are bad – and they do know where they are.”

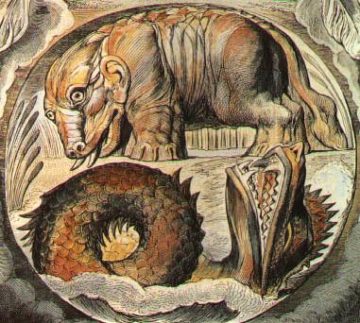

Frontispiece of Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan, 1581.

The New York Times published an article covering Trump’s speech dramatically entitled, “Blaming Muslims After Attack, Donald Trump Tosses Pluralism Aside,” in which Jonathan Martin and Alexander Burns noted that Trump’s “language more closely resembled a European nationalist’s than a mainstream Republican’s,” and described him as “flouting traditions of tolerance and respect for religious diversity.” Even Republicans have accused Trump of uncivilized behavior:

“Everybody says, ‘Look, he’s so civilized, he eats with a knife and fork,’” said Mike Murphy, a former top adviser to Jeb Bush. “And then an hour later, he takes the fork and stabs somebody in the eye with it.”

Both Trump and the New York Times cast the civilized nation-state of the United States as the protagonist of their stories. The Times just happens to include Trump in its list of those who threaten “American traditions,” whereas Trump would list Mexicans and Muslims instead. But not all storytellers consider civilization itself to be a protagonist.

In his 1983 book Against His-story, Against Leviathan, Fredy Perlman questions the entire narrative of civilization. Perlman borrows the term “Leviathan” from the authoritarian political theorist Thomas Hobbes, who described the organization of human societies into a “great Leviathan called a Commonwealth, or State, in Latin Civitas, which is but an artificial man” (qtd. in Perlman 26). Hobbes’s “artificial man” bears an uncanny resemblance to what Karl Marx called capital: “Capital is dead labor, which, vampire-like, lives only by sucking living labor, and lives the more, the more labor it sucks.” Perlman, too, describes a leviathan as a carcass “brought to artificial life by the motions of the human beings trapped inside.”(27)

In his 1983 book Against His-story, Against Leviathan, Fredy Perlman questions the entire narrative of civilization. Perlman borrows the term “Leviathan” from the authoritarian political theorist Thomas Hobbes, who described the organization of human societies into a “great Leviathan called a Commonwealth, or State, in Latin Civitas, which is but an artificial man” (qtd. in Perlman 26). Hobbes’s “artificial man” bears an uncanny resemblance to what Karl Marx called capital: “Capital is dead labor, which, vampire-like, lives only by sucking living labor, and lives the more, the more labor it sucks.” Perlman, too, describes a leviathan as a carcass “brought to artificial life by the motions of the human beings trapped inside.”(27)

Perlman notes that the human beings within the earliest leviathan, that of Sumer, “still seek contact with the spirits of the winds, the clouds, even of the sky itself,” and that this continued contact with the spirits and gods “is probably what accounts for the exoticism that will continue to cling to what we will call ‘early civilizations.’”(23) Later in his narrative, Perlman writes that the commandment “thou shalt have no other gods before me” is a precursor to modernity: “this is modern.”(57) He writes that monotheism is Moses’ “inner emptiness, his armor, his own dead spirit” projected “into the very Cosmos.”(56)

In Perlman’s analysis, leviathans expand by conquering and subsuming more and more human beings. Naturally, many human communities attempt resistance, either by fleeing or fighting. Perlman describes the decision to stay and fight in eloquent animist terms:

Not all communities want to flee. Their valleys, groves and oases, the places where their ancestors are buried, are filled with familiar and often friendly spirits. Such a place is sacred. It is the center of the world. The landmarks of the place are the orienting principles of an individual’s psyche. Life has no meaning without them. For such a community, leaving its place is equivalent to committing communal suicide. So they stay where they are. And they are kissed by the monster’s grotesque lips.(32)

Unfortunately, as these communities attempting resistance build their own permanently walled cities and establish their own permanent standing armies, “soon there are many Leviathans.”(34) The resisters turn into precisely that which they had attempted to resist, and they develop what Wilhelm Reich called “character armor.”

William Blake, “The Body of Abel Found by Adam and Eve,” 1826.

Perlman uses terminology borrowed from Zoroastrianism to describe the need to shed this internal armor:

Zarathustra reduced Hesiod’s five generations to two: one is outside the Leviathan, the other is inside. The outsider is Light, Ahura Mazda, associated with the spirits of fire, earth and water, with animals and plants, with Earth and Life. Ahura Mazda is the strength and the freedom of the generation Hesiod considered the first, the golden.

The insider is Darkness, Ahriman, also called The Lie. Ahriman is the Leviathan as well as the Leviathanic armor that disrupted the ancient community. […]

Ahriman is in the world and in the individual. The war against Ahriman is waged in the world and in the individual. It is simultaneously a struggle against Leviathan and against the armor. It is waged with fire, the great purifier. The mask is burned off, the armor is burned out, the Leviathan is burned down. And woe to the world if the fire should fall to Ahriman, to the hands of armored men!(77)

Of course, the fire does indeed fall into the hands of armored men, and subsequently, the clashes of rival leviathans are deceptively framed as cosmic battles of good and evil, where one’s own leviathan or civilization is “on the side with the angels,” while “the wilderness is elsewhere, barbarism is abroad, savagery is on the face of the other.”(1) That is precisely what we see today, with Trump, with Clinton, with the New York Times. Tellingly, Perlman begins his entire book with an epigraph from Matthew Arnold:

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight

Where ignorant armies clash by night.(1)

A Darkling Plain

In an interview in The Atlantic, “The Meaningless Politics of Liberal Democracies,” Shadi Hamid argues that “there’s a general discomfort among American liberals about the idea that people don’t ultimately want the same things, that there isn’t this linear trajectory that all peoples and cultures follow: Reformation, then Enlightenment, then secularization, then liberal democracy.” He says that political Islamist movements (which vary widely in their interpretations and applications of Islamic law to politics) often “don’t ultimately want the same things” as American liberals, and that these differences should be acknowledged and respected:

As political scientists, when we try to understand why someone joins an Islamist party, we tend to think of it as, “Is this person interested in power or community or belonging?” But sometimes it’s even simpler than that. It [can be] about a desire for eternal salvation. It’s about a desire to enter paradise. In the bastions of Northeastern, liberal, elite thought, that sounds bizarre. Political scientists don’t use that kind of language because, first of all, how do you measure that? But I think we should take seriously what people say they believe in.

Hamid also states that rise of “ideology, religion, xenophobia, nationalism, populism, exclusionary politics, or anti-immigrant politics” all signal a widespread loss of faith in secular liberal democracy. He says to the interviewer, “the question of whether it’s good or bad is beside the point […] I see very little reason to think secularism is going to win out in the war of ideas.”

William Blake, “Behemoth and Leviathan.”

Hamid’s analysis isn’t too dissimilar from that in the New York Times in seeing xenophobia and nationalism as rejections of liberalism, but unlike the Times article, his approach is to analyze the reasons why this may be happening. In Fredy Perlman’s words, “Leviathan, the great artifice, single and world-embracing for the first time in His-story [sic], is decomposing” (301).

Like Perlman, Hamid also understands that violence is central to state building. Therefore, the question of whether Islam as a whole is violent or not is a strange one to him:

A question I get a lot is, “Wait, ok, is Islam violent? Does the Quran endorse violence?” I find this to be a very weird question. Of course there is violence in the Quran. Muhammad was a state builder, and to build a state you need to capture territory. The only way to capture territory is to wrest it from the control of others, and that requires violence. This isn’t about Islam or the Prophet Muhammad; state building has historically always been a violent process.

Perlman writes that although the world-embracing leviathan is now decomposing, “being above all else a war engine, the beast is most likely to perish once and for all in a cataclysmic suicidal war.”(301) We see today an “array of competing actors” in Syria, that battleground that has become emblematic of our times, one where “opposition groups frequently merge and disassociate, producing a dynamic churn that makes understanding the opposition challenging.” These days, the question of “sides” in spiritual and cultural warfare is only relevant if one speaks of the ancient struggle of human communities against leviathan. The decomposition of one leviathan into many little leviathans is no longer particularly interesting.

William Blake, “Oberon, Titania and Puck with Fairies Dancing,” circa 1786.

“People waste their lives when they plead with Ahriman to desist from extinguishing the light.”(301) However, Perlman writes of another vision as well, one which does not involve another armored leviathan rising from the ashes as so many have before:

In ancient Anatolia people danced on the earth-covered ruins of the Hittite Leviathan and built their lodges with stones which contained the records of the vanished empire’s great deeds. The cycle has come round again. America is where Anatolia was. It is a place where human beings, just to stay alive, have to jump, to dance, and by dancing revive the rhythms, recover cyclical time.(302)

The Orlando shooting took place at an LGBTQ+ nightclub. It wasn’t just an attack by one leviathan against another. It was an attack on human beings, on human community, on dancers, on “kinship and community,” on those who “still have an ‘inner light,’ namely an ability to reconstitute lost rhythms, to recover music, to regenerate human cultures.”(301)

* * *

This column was made possible by the generous underwriting donation from Hecate Demeter, writer, ecofeminist, witch and Priestess of the Great Mother Earth.